This year’s Earth Day and the COVID-19 Pandemic have shown us how interconnected we are not only to one another, but also to the natural world at large. Although the environment has been a source of inspiration for artists for centuries, in recent years contemporary artists have been faced with the inescapable effects of our climate crisis, from rising water levels to raging wildfires. According to the UN, greenhouse gas emissions from human activities are now at their highest levels in history. It is no surprise that artists today feel a responsibility to use their work as a platform to raise awareness of climate change issues and envision a more sustainable future, rather than simply creating visual replicas of the natural world as we have seen throughout history. Here we explore five artists who are leading players in this space, having taken up the challenge of creating symbols potent enough to break through into public consciousness.

BLUE believes that the actions we take over the next decade could be the key to avoiding climate disaster, which is why we are encouraging more artists such as these to become part of the conversation, and why we are donating 5% of all BLUE’s profits to the World Land Trust.

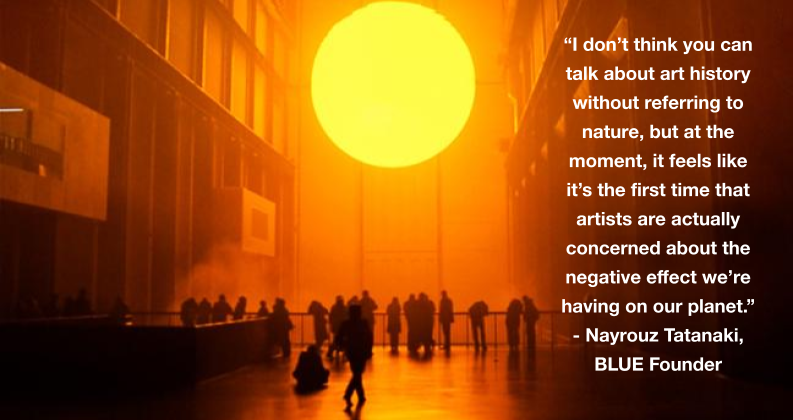

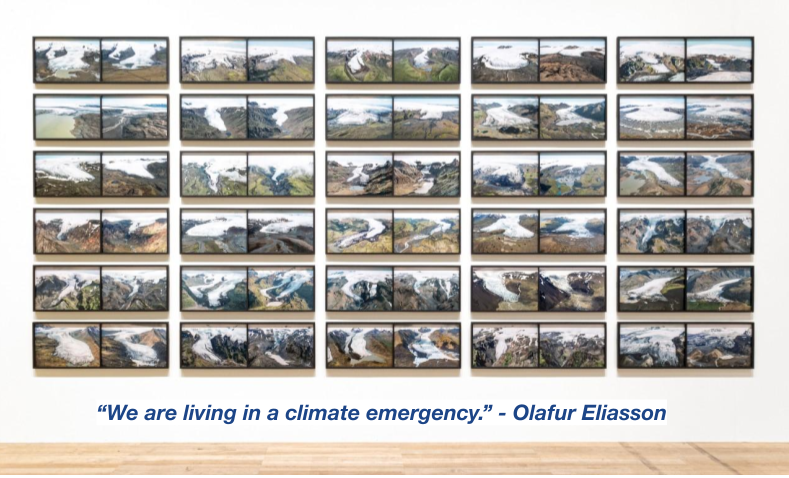

Olafur Eliasson

A lot has happened in the two decades since Eliasson documented Iceland’s endangered glaciers, as can be seen with The Glacier Melt Series 1999/2019. Bringing together thirty pairs of images from 1999 and 2019, Eliason dramatically reveals the impact that global warming is having on our world. Eliasson, who was appointed as a Goodwill Ambassador for climate action in 2019 by the United Nations Development Programme, has dedicated his career to finding ways to encourage us to reconnect with the natural world and preserve it, from secretly dying the rivers and canals in cities across the world, to creating a fake sun in the Tate Modern. As well as drawing attention to climate change through his work, Eliasson also demonstrates an awareness of the carbon footprint of the international art world. At Olafur Eliasson’s 2019 Tate Modern show, a handwritten note inside the final room displayed the message “artworks have carbon footprints, too”, presenting museum visitors with an arrestingly ironic and contradictory message.

Agnes Denes

Agnes Denes was one of the pioneering artists to explore humanity’s unsustainable relationship with the natural world, tackling the subject in her art for over half a century. In 1982, Denes planted around two acres of wheat in downtown Manhattan at the old Battery Park Landfill, to create Wheatfield—A Confrontation, which highlighted the tension between the field and the city behind it. As the crop grew, so did a new landscape punctuated by golden waves of pastoral grain, contrasted against the built-up Financial District on one side and the Statue of Liberty on the other. The crop yielded over a thousand pounds of grain, which traveled to 28 cities around the world in an exhibition titled “The International Art Show for the End of World Hunger.”

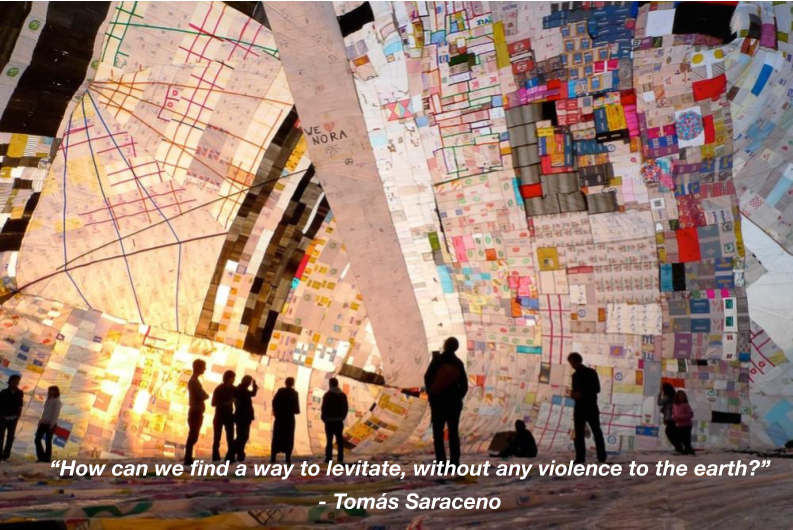

Tomás Saraceno

Like Agnes Denes, Saraceno combines art with science and sociology, to envision a more sustainable existence. Over the past decade, Saraceno has been developing what he calls “collaborations with the atmosphere” within his project Aerocene (2015–present). Through this collective, Saraceno has created floating, solar-powered museums made entirely of recycled plastic bags (Museo Aero Solar, 2007–present), and in 2015, the group broke a world record for the first and longest fully solar-powered flight.

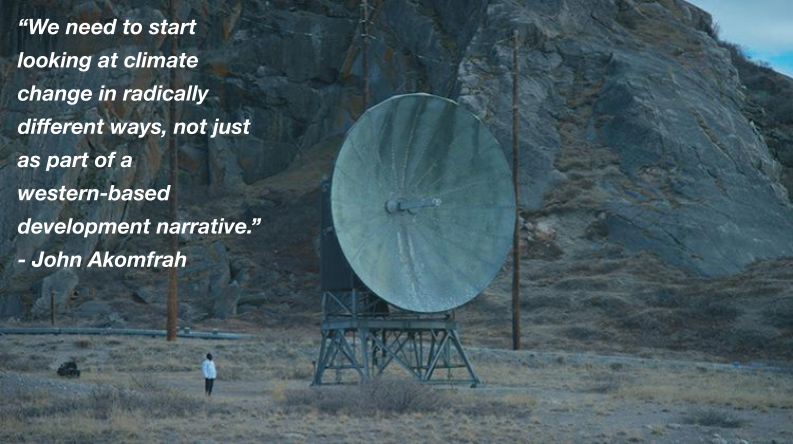

John Akomfrah

John Akomfrah’s Purple (2017) is an immersive 6-channel video installation that was filmed across 10 countries, exploring climate change, human communities and wilderness. This work brought a multitude of ideas into conversation, including animal extinctions, the memory of ice, the plastic ocean and global warming. Stretching from the industrial age (images of factories, mills, machines and mass employment) to the digital revolution and beyond (the possibilities promised by biotech research, artificial intelligence and genetics), the threat of ecological disaster is implicit throughout, symbolised by recurring figures in white who gaze ominously at landscapes disrupted by human progress.

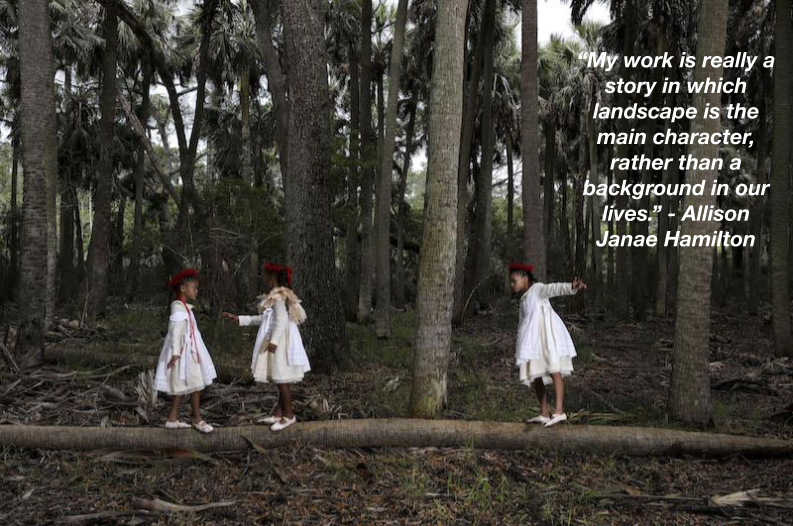

Allison Janae Hamilton

Through her investigations of American landscapes, Hamilton asks us to consider social relationships to space in the face of a changing climate, particularly within the rural American south. By drawing on the social histories imbued in our landscapes, Hamilton highlights how the natural world can expose deeply embedded histories of race and inequity. In Hamilton’s treatment of land, the natural environment is the central protagonist, not a backdrop, in the unfolding of historic and contemporary narratives.